Is "Good Enough" AI, actually Good Enough?

Sometimes the debate isn't "AI vs. expert," but "AI vs. nothing." This view aids access but risks a two-tier system, reinforcing inequality with a lesser standard of care for the under-served. The solution is augmentation, not replacement, using AI to scale, not substitute, expert services for all.

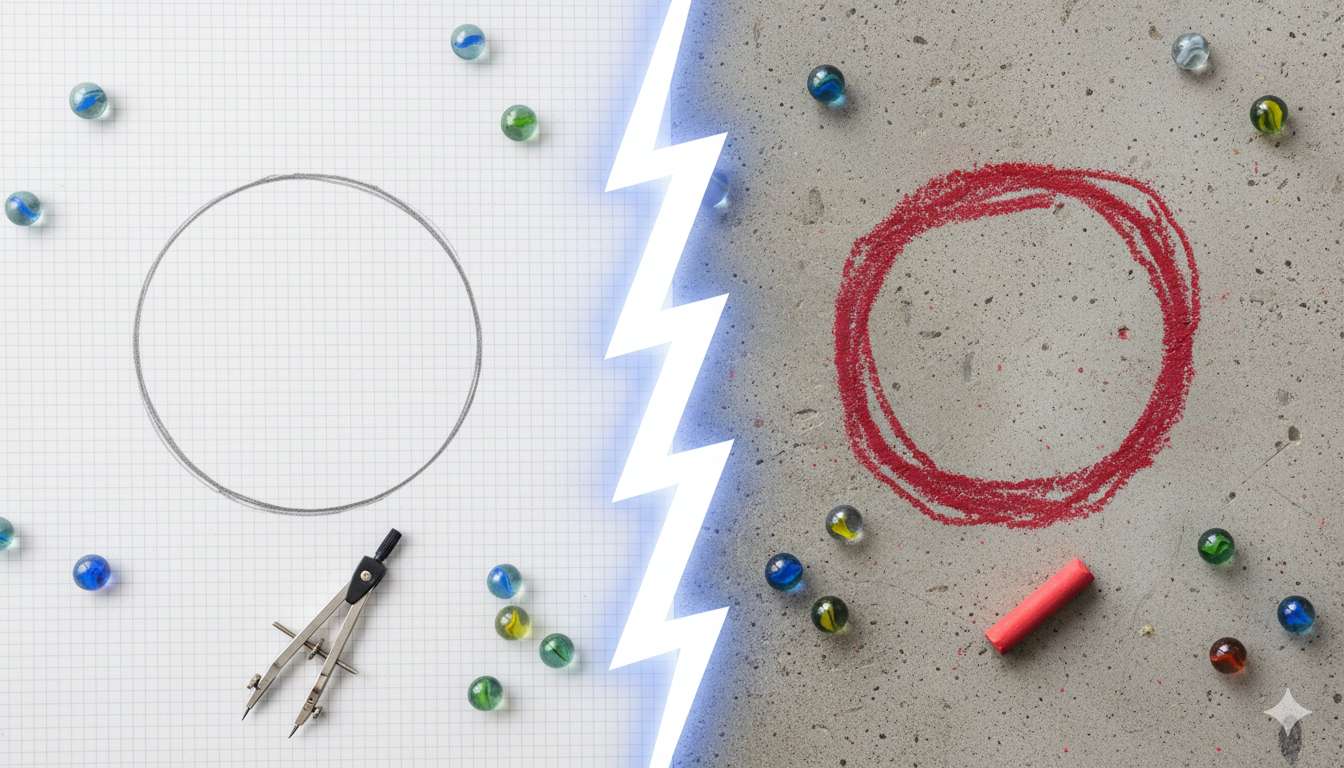

The Wrong Goalposts for AI

Critics of current AI agents are quick to point out their flaws—they hallucinate, they lack nuance, their advice can be dangerously incorrect. These criticisms, while valid, are asking the wrong question. They measure today's nascent technology against a hypothetical ideal of perfect human expertise, missing two things we have learned from every major technology adoption cycle.

First, the capability of these systems improves at a rapid rate. Today's limitations are not a reliable guide to tomorrow's potential. Early mobile phones were derided as impractical bricks, and the first internet search directories were hopelessly naive compared to what followed. Technology evolves.

Second, and far more consequentially, these critiques come from a position of privilege. For a significant portion of the global population, the alternative to an imperfect AI is not a world-class doctor or a seasoned lawyer. The alternative is nothing.

The Real-World Benchmark: AI vs. Nothing

When we reframe the comparison, the value proposition of AI shifts entirely. Is an AI agent that can provide a decent first draft of a business contract, even one that needs review, better than having no legal document at all for a startup in a developing nation? Is an AI that offers plausible explanations for medical symptoms, while urging a visit to a clinic, worse than having no information when the nearest doctor is a day's journey away?

The debate should not be "Is ChatGPT as good as a lawyer?" but rather, "Is it a better option than navigating a complex legal issue with no guidance whatsoever?"

This is not a theoretical exercise. People are already using these tools to diagnose illnesses, draft legal notices, and seek financial advice. The reality on the ground is that AI is filling a vacuum of access created by the scarcity and cost of human experts. To ignore this is to ignore the primary driver of its adoption. For many, a "good enough" answer today is infinitely better than a perfect answer that is perpetually out of reach.

The Professional's Dilemma: When "Do No Harm" Meets "Do Nothing"

This new reality creates a profound challenge for established professions governed by strict ethical codes. Fields like medicine and law are built on a bedrock of accountability, rigorous training, and a duty of care, encapsulated by principles like the Hippocratic Oath's "first, do no harm."

How do such frameworks, designed for a world of scarce, human-delivered expertise, adapt to a world of abundant, non-human, and imperfect advice?

This forces us to ask uncomfortable but necessary questions:

- Does the principle of "do no harm" extend to preventing access to a tool that, while imperfect, could provide benefit to someone with no alternative? At what point does withholding a potentially helpful tool become a harm in itself?

- Where does accountability lie when an AI provides flawed advice? The fear of liability is a, sometimes useful, brake on innovation. If we demand perfection before deployment, we may paralyze the development of tools that could democratize access to critical knowledge.

- Are we inadvertently sanctioning a two-tiered system of expertise—human professionals for the affluent and AI for everyone else? Or is AI the only viable path to providing a foundational level of service and knowledge to under-served populations?

These are difficult questions with few easy answers. They represent a conflict between established ethical standards and the urgent, real-world need for access. Professionals are rightly concerned about the risks of misinformation and the erosion of standards. Yet, defending a status quo that excludes billions from essential services is not a tenable long-term position.

A Path Forward: From Gatekeeping to Guardrails

The solution is not to block progress but to guide it. The goal is not to replace human experts, but to augment them and, crucially, to fill the vast gaps where no expert is available. As a technologist, I see this not as an intractable ethical problem, but as a systems design challenge.

We must shift our focus from demanding perfection to engineering safety and reliability at scale. This involves:

- Building Effective Guardrails: Instead of asking if an AI can replace a doctor, we should be building systems that can reliably answer low-risk questions and, most importantly, recognize their own limitations. The system must know when to say, "This question is beyond my capabilities; you must consult a human professional."

- Creating Triage Systems: AI can serve as a powerful front door, an initial point of contact that helps individuals organize their thoughts, understand their options, and prepare for a more productive conversation with a human expert. This optimizes the valuable time of professionals, allowing them to focus on high-judgment tasks.

- Innovating in Regulation and Liability: We need new legal and regulatory frameworks that foster responsible innovation. This could include certification for AI agents in specific domains or "safe harbor" provisions for tools that meet rigorous transparency and safety standards.

The discourse around AI's imperfections is a distraction from the more pressing task at hand. We must stop judging this technology against an unachievable ideal and start evaluating it against the stark reality of the alternative. The critical challenge for leaders, regulators, and professionals is to build the frameworks that allow us to leverage "good enough" AI safely, ethically, and at a global scale.